Rugby is a martial sport. It has forward battles and blitz defences and high kicks known as bombs. On TV, captains are asked about their men. In deadly earnest, they answer: “With these guys, I’d go to war.”

Pete Chacon was a member of the West Point class of 2002, the first to graduate the United States Military Academy in wartime since the days of Vietnam. In Iraq in 2004, he commanded a rifle platoon in the Battle of Mosul.

In 2015, asked to remember, he thinks a moment. Perhaps he thinks of when he was wounded, when he “ate” an IED “with my face and half my body”. Perhaps he thinks of a friend who didn’t come back.

But then he says: “I loved everything about it. I was surrounded by some truly great people. The kind of guys you’d want to play rugby with, you know?”

Rugby union has been played at West Point since 1961. The honour roll of players killed in combat is long. Above the locker-room door at the Anderson Rugby Complex, one word leads to the field: “Brothers.”

It is drawn from Henry V: “He to-day that sheds his blood with me, shall be my brother.” At West Point, rugby players treat Shakespeare’s words as an oath. Some wear them, tattooed, on shoulder, breast or thigh.

It is a unique spirit. One night in the spring of 2002, at a military sports ground near London, I had a taste of it.

I played lock forward for the Rosslyn Park club, against the touring cadets. It was a fast game, played under lights. Trained for warfare, superbly fit, the Americans kept on coming.

Afterwards, in a military bar, the two teams mixed. My opposite number, an enormous cadet named Bryan, gave me an appropriate gift: a shot glass engraved with the West Point emblem, the helmet of Pallas Athena. War and wisdom.

Six months had passed since 9/11; five since the invasion of Afghanistan. As time went on, as Bush turned his gaze on Iraq, the game stayed lodged in my mind.

The months stretched to years, the years to a decade and more, and America’s wars went on. The questions remained. What happened to those West Point rugby players? Did they fight? If so where, and how? Did they live or die?

By the summer of 2015, I was settled in New York. America’s ground wars were approaching their end. It seemed a good time to find out.

To take the train from New York City to West Point is to travel in time and American lore. Out of Grand Central, the stations slide past. Spuyten Duyvil, where Henry Hudson dropped anchor. Croton, which gave Gotham its water. Ossining, home of Don and Betty Draper.

At Peekskill, the roads take the traveller west, and soon the granite towers of West Point appear, looming over the motels of Highland Falls. This is where, since 1802, the US army has made many of its officers.

On a humid day in May, Mike Mahan welcomed me into his office. A retired lieutenant colonel, Coach Mahan is West Point rugby. Or rather, was. When I met him, he was preparing to step down, 25 years after first taking the helm.

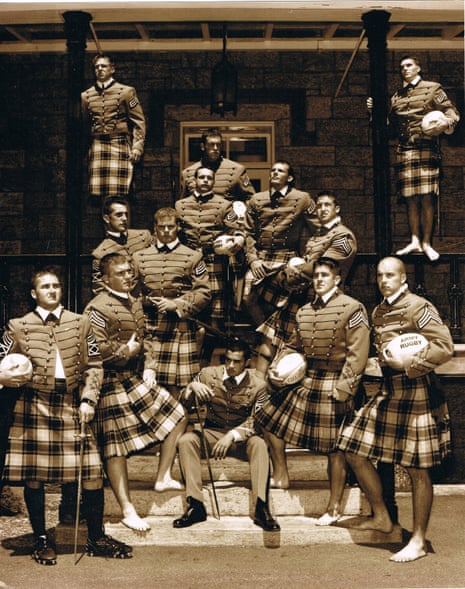

Among cartons and cases, I talked with Mahan, two players, Jack Ireland and Logan Pearce, and 2004 graduates Brent Pafford and Mike Ziegelhofer, now majors with long service records. On Mahan’s table, there was a framed photograph. It was taken 13 years before, not long after the game against Rosslyn Park. The class of 2002.

On granite steps, 13 cadets struck heroic poses, appropriate to the sepia tone. They wore grey uniform jackets and kilts, and carried sabres. They also carried rugby balls. Pete Chacon was among them, sitting on the bottom step, looking intently to his right.

These men entered West Point in peacetime. They left with their country at war. By the time I looked at their picture, many were out of the army. In Texas and Oklahoma a second row, a wing and a flanker prospected for oil and gas. In Missouri, a centre sold defibrillators. In Massachusetts, the full-back and captain worked in investments.

Others were still serving. In Georgia, a pilot trained his successors. In Virginia, the No8 shaped national missile defence. In North Carolina, a prop with no less than nine tours as a US Ranger – six to Afghanistan, three to Iraq – worked at Joint Special Operations Command.

In New Jersey, Pennsylvania and California, three young men were remembered.

I called my opposite number first. Down the line from Houston, where he had finished business school while working for an energy company, Bryan Phillips confirmed the size of the impression he’d made.

“At the time I was 6ft 8in and about 300lbs,” he said. He laughed, ruefully. “I’m sorry to say I weigh a little bit more than that now.”

At 35, Phillips was considering a return to the field, having been one of the few brothers to play rugby seriously – for Houston Athletic – after leaving West Point. Later, over beer and oysters in Duxbury, Massachusetts, his old captain, Matthew Blind, told me Phillips may have been playing modest: he now ran marathons.

Phillips’ route to rugby was that of most of his team-mates. He arrived at West Point a football player, aiming to Beat Navy. Cut from the squad, he switched to the other oval ball.

“I fell in love with it,” he said, “especially being an offensive lineman in football where you don’t get to tackle anyone and you don’t get to touch the ball. And there was the brotherhood. Rugby was absolutely all for me.”

Rugby is a game for all sizes. Blind, the full-back, started West Point a youthful 5ft 6ins and 165lbs, a roommate who presumably slept in any air pockets not filled by Phillips. He was a cornerback until he discovered rugby. Jerrod Adams, another welterweight, was a free safety who became a wing. Dave Little was a linebacker who switched to No8, “got punched in the face a few times and fell in love”.

Brian McCoy was a football fullback turned flanker who spent his first game of rugby, at the Royal Military College of Canada, “breaking every rule there was”. “I didn’t know there were rules,” he said. “I blocked as much as I could, I hit with my head, I did everything that was bad for my body. And I fell in love with the game.”

Chacon and Jeremiah Hurley, the Ranger, were wrestlers who became a wing and a prop. The centre Clint Olearnick, unique in having played before West Point, said wrestling gave Hurley “the purest tackling technique on the team”.

Between them, with relish, the cadets embraced their sport and their bond.

“The first tattoo I ever got is a sword and shield through a rugby ball that says ‘brothers’ on it,” said Phillips. “It’s on my right shoulder. It was drawn by Brian McCoy and a lot of us have versions of the same tattoo. It has an XV on it” – for the number of men in a rugby team – “and a V for my number.”

McCoy’s sketch contributed to an enduring tradition. When I visited West Point in May, Logan Pearce sported his version of the tattoo, a KA-BAR knife through a rugby ball, wrapped with “He today who sheds his blood with me” and emblazoned with “brothers”, on his thigh. When I went back in September, new captain Donny Goff had the same design.

Each member of the class of 2002 said the bond remained strong, whether through weddings, godparenting or the chance to grab a beer when business landed two players in the same airport bar.

“All we really had was each other,” said Chacon. “And that was I think a large part of that was Coach Mahan’s style. He taught us to fight for the man next to you, to be a brother and to be selfless.

“You know, that pays dividends in a combat situation. He wasn’t just teaching us about rugby … he was building leaders.”

Blind said: “The guys who were really the core of that rugby team, I still consider them my best friends. I feel I could pick up the phone with any problem I had today and they would jump through hoops to help me.

“As great as the sport is and as great as winning was, and as great as the fun and the camaraderie and the partying was, the brotherhood was the most important thing. To know you’ve always got someone you can rely on. No questions asked.”

Zac Miller was a lock forward from Sandy Lake, Pennsylvania. On arrival at West Point as an unwitting high-school lineman, his mother told me, he found himself “coerced” by a rugby-loving officer.

Miller was a leader, and a bright one: “brilliant” in Blind’s words, “presidential material” in Mahan’s. Accordingly, he was headed for an internship in Washington, with the Pennsylvania senator Arlen Specter. A Truman scholar, he finished top of his class in math, computer science and basic science, 11th overall.

In March 2002, West Point celebrated its bicentennial. The TV cameras came, and Miller was interviewed by Anderson Cooper. What was the toughest thing about the academy, the CNN anchor asked. It was not his military training, Miller said. It was not his double major. It was “being on the army rugby team … going out to practice every day, being challenged by your team-mates”.

His comment attracted the puzzled attention of West Point’s commanding officer. That night, at a celebratory dinner at the Russian Tea Rooms in New York City, Miller was collared and questioned by Lieutenant General William Lennox himself. He passed the interrogation.

Miller had already spent a summer with the army in Germany, but unlike most bicentennial graduates he was not heading straight into uniform. He had won a Rhodes scholarship and was on his way to Oxford, to study politics, philosophy and economics. First, though, he wanted one more challenge.

Ranger School, held in the heat of Fort Benning, Georgia, is a notoriously tough examination. As Coach Mahan told it, softly spoken over the sepia seniors’ photograph, one hot day, 1 July 2002, Miller did not return from an exercise. He was found, Mahan said, sitting on a log with his helmet off, having attempted one last task. He died of heat exhaustion. He was 22.

Miller’s parents, Rosalyn and Keith, now run a foundation in their son’s name. Among other commitments, they donate to West Point rugby. In the locker room at Anderson, thanks to another donor, a plaque bears his name. Appropriately, it sits above the bench used by another second-row forward, John Sproul.

“Zac loved rugby,” Rosalyn Miller told me. “And he thrived at West Point. I still have the T-shirts he wore, which say ‘Brothers, Army rugby’. We have that on his grave marker too.”

Joey Emigh was an inside-centre from Fullerton, California, as laid-back in manner off the field as he was intensely driven on it.

When Clint Olearnick discussed his friend and back-line partner, his words struck echoes about how their sport related to officer training and combat. On the field, Olearnick said, “in the centres, you rely on the guy inside you. Nothing ever got past Joey.”

Emigh, like so many, went to West Point to play football. Injury curtailed his time on the squad. Ensconced in the rugby team, he was at the centre of most of its decisions – including the call, in France on a tour in which, Jerrod Adams said, “we had our share of fun” – to pick up and move a small car that was blocking in the bus.

“The rugby brotherhood was everything to our Joey,” his mother, Joanne, told me. “Because he didn’t have a brother at home.”

On 2 September 2002, while he was on leave before posting to field artillery, Emigh died in an accident, drowned in a lake near Houston. He was 23.

“I remember the day,” said McCoy. “We were at flight school, when [Emigh’s father] George called me and said they’d found a body and they’re pretty sure it’s Joey. I remember taking the call, the house we were at. We had all the boys up from Fort Benning, it was a weekend. And most of us were probably drunk and just sitting in sorrow.”

George and Joanne Emigh told me that when Joey found rugby, this strange sport found them too. At West Point, the game did not just bring players together. It formed bonds between their parents. When the team went to Europe, the Emighs tagged along.

“We still follow army rugby,” George Emigh said. “Though we still don’t know all the rules.”

Emigh’s centre partner, Olearnick, was maybe the best rugby player in the class of 2002. A Coloradan, after West Point he played on through close to 12 years as an infantry officer and three tours to Iraq. Out of the Kansas City Blues, he played for the All-Army team and reached the US Eagles’ player pool.

At West Point, Olearnick became close friends – in McCoy’s words “nearly inseparable, hand in glove” – with another former football player. He was from Eatontown, New Jersey, and he was loathe to add weight to play linebacker. Instead, he became the heartbeat of West Point rugby. He played hooker, and his name was Jimmy Gurbisz.

On a baking August morning, I visited his home town. On the Coastal Line from Penn Station, past the meadowlands and the battered industry of Secaucus, Newark and Elizabeth, a different Jersey revealed itself: green, watered and prosperous.

Gurbisz’s father, Ken, drove me to Monmouth Regional High School. The Falcons’ Hall of Fame was decked in black and gold – coincidentally, the colours of West Point. Under a commemorative plaque, Jimmy Gurbisz’s football and baseball uniforms were framed.

Ken Gurbisz’s son began his life here, hard by Fort Monmouth, a vast army base now shuttered and ready for sale. Growing up the son of a Vietnam veteran, he wanted to go to West Point. After that, he wanted to join the infantry.

Rugby, however, pointed him another way. It happened in Virginia Beach in May 2002, at the national final four.

“It had been raining and his cleat got stuck in the mud,” Ken Gurbisz said. “He got hit and it turned his knee. It was his ACL, he tore it. They said it wasn’t that bad, but it never really healed properly.

“He branched infantry, after 9/11 … and when he was down at Fort Benning [his knee] started acting up. The last day of his infantry training was a two-mile run, and it was a very cold, damp day. And he finished the run but he didn’t do it in the prescribed time.

“He was limping badly, he wound up having microfractures on his femur. So he had surgery and was sidelined for over six months … and he couldn’t be an infantry officer. He was devastated.”

Posted to Baghdad as a transport officer, Gurbisz volunteered for convoy security. In the war of the roadside bomb, it was a dangerous thing to do.

According to US Central Command, 6,828 US troops have died in Iraq and Afghanistan. Thousands of allied troops, contractors and police have also been killed. According to estimates by the Watson Institute of International Affairs at Brown University, by January 2015 165,000 Iraqi civilians and 26,000 Afghan civilians had met with violent deaths.

Asked if America’s wars had been worth such a toll, the West Point rugby players gave similar, careful answers. Maybe, maybe not. It was a subject for serious debate – for one beer or two or more. Brian McCoy’s answer was typical.

“If it’s a question of right and wrong,” he said, “and did we do the right thing, I would say the answer was yes.”

The West Point motto, after all, is “duty, honor, country”. McCoy, though, wasn’t done.

“There was enough political uncertainty,” he said, “to last for the rest of my life.”

Asked about Jimmy Gurbisz, each player grew similarly thoughtful. When they spoke, they agreed: he was the heart of the team, a cadet committed – to the point of cheerful lunacy – to rugby and the brotherhood.

They remembered his role in Coach Mahan’s intense training sessions, up at the top of a brutal 50ft bluff up which cadets still run, there to ring a bell hung with the dog tags of the rugby players who died. They remembered suicide sprints, tackling drills and rucking practice, up there by the old PX.

In the days before Anderson Rugby Complex was built, long before rugby gained varsity status, that patch of ground – too short for rugby, sloping, not even fully grassed – was also used for tailgating at football games. It was thus covered, in Hurley’s words, in “broken beer bottles, bottle tops, rocks and vomit”.

In such a place, Phillips said, “Jimmy was that guy, the guy who drove us on”.

Chacon put it more forcefully: “Oh my God, Jimmy was a maniac on the training field. I don’t think he knew what pain was. He was wired differently than the rest of us. He just didn’t stop. He was always in fifth gear.”

In Eatontown, Ken Gurbisz looked 10 years into the past. “Jimmy went to Iraq in January 2005 and was there 10 months,” he said.

By then, the rugby players had taken many paths. McCoy and Jerrod Adams were pilots, McCoy based in Italy, flying rotary-wing aircraft, Adams flying Apache helicopters and heading for Iraq. Phillips and Little were air defence artillery, their jobs largely done in the first few days of the war, when in Little’s words they “shot down all the Scuds”. Hurley was a Ranger and Olearnick, Chacon and Blind were infantry, fighting on the ground in Iraq.

“We talked to Jimmy last a couple weeks before he was killed,” said Ken Gurbisz. “He was really kind of getting hyped about coming home. They said it was quiet at the time.”

Captain James Gurbisz died in Baghdad on 4 November 2005, when his Humvee hit an IED. He was married to his high-school sweetheart, Victoria, and he was 25 years old. His driver, Private First Class Dustin Yancey, died with him. He was from Goose Creek, South Carolina. He was 22.

When they heard, the rugby players were shattered. Hurley’s wife, Dawn, another West Point graduate, had been stationed with Gurbisz at Camp Rustamiyah. Chacon was also in Iraq. For the funeral, at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, McCoy flew in from Italy. A group of players were pallbearers.

Olearnick wasn’t there. He remembers the moment his room-mate in Iraq told him Gurbisz had died as “the hardest thing”. But because Gurbisz had not been in his unit, the army would not allow him the leave.

“It was one of those army things,” he told me with a diplomatic sigh, down the line from St Louis. “I wish I would’ve been able to make it …”

By phone from Oklahoma, Chacon said “it was hard. I was there, in Baghdad, at the time that it happened. And … ”

His voice trailed off. He collected himself.

“There weren’t too many guys like Jimmy.”

In Eatontown, such words were repeated. At the high school and in Wampum Memorial Park, next to the stone doughboy and the monuments to Vietnam and the second world war. At the little league field, by a plaque inlaid with pictures of Gurbisz as soldier and slugger. At Applebee’s, where his West Point graduation picture looked over a booth, emblazoned with the words: “Thank you, real heroes.”

The message was the same, whether spoken by Ken and Helen Gurbisz, baseball coach Ted Jarmusz or Andy Teeple, once Jimmy Gurbisz’s calculus teacher, now superintendent. Captain Gurbisz, in whose name his parents now run their own charitable foundation, was a remarkable young man.

Other rugby players died, including some who played with the class of ‘02. Benjamin Britt, from the class of 2004, was on patrol in Baghdad when an IED exploded. John Hortman, also 2004, died when his helicopter crashed in training. Tom Martin, 2005, died of wounds in Iraq. In 2011, Dimitri Del Castillo, class of 2009, died in a firefight in Afghanistan.

Amidst it all, the players of 2002 remember their team-mates, the games they played and the sights they saw.

Some hold on to mementoes. On the wall of his basement gym in Scituate, Massachusetts, Matt Blind has a Rosslyn Park shield. “Somewhere upstairs” in his North Carolina home, Jeremiah Hurley has “the stones we collected on the beach”.

The beach was Omaha, in Normandy, where on D-Day in 1944 US forces fought their way ashore. The cadets visited after beating the French academy, St Cyr, on the way to Rosslyn Park and a crunch game at Sandhurst – with appropriately heroic post-game socialising, Blind working the bar, Adams surviving “my first game of naked rugby” – against the Royal Military Academy. For a group of young men who knew others already in Afghanistan, it was a sombre day.

“By that time Saving Private Ryan was out and we had a visualisation of warfare,” Bryan Phillips said. “We all knew something was going to happen, post-9/11. We just didn’t quite know what.”

More than one brother mentioned Steven Spielberg’s film. Others mentioned the HBO hit Band of Brothers. They all mentioned their awed appreciation of what their predecessors had done, 60 years before.

“When we got to Omaha beach it was low tide,” said Brian McCoy. “Me and Joey Emigh walked all the way out to the waterline, where you couldn’t go any further, and then we turned around.

“And it was Joey and I, just seeing the vast amount of beach that had to be covered, and looking at the pillboxes and what a disadvantage those soldiers were at. That it is something I will never forget.”

When I went back to West Point in September, a day after the 14th anniversary of 9/11, I met Coach Mahan again. On a thundery, close afternoon, a new team played for a new leader: Matt Sherman, once an Eagles fly-half. While the brothers of 2015 ran Buffalo ragged, the man Jerrod Adams said “was really our father” looked on from the Anderson stands.

“2002 was a very special class” Mahan said. “They really were a microcosm of army rugby. We had brilliant scholars and tremendous athletes, and they bonded together.”

Mahan was about to move back to California. His flight would take him over many of the men he coached. Thirteen years on, the members of the class of 2002 were still young, not even midway upon the journeys of their lives. But in the years after 9/11, in different ways and with different links to those who died, they all looked into the inferno.

“The tragedy of losing three American men like that is just awesome,” said Mahan, who spoke at all three funerals. “For it to happen within one class is very sad.”

On an internet memorial page for Jimmy Gurbisz, I found the following lines:

“I miss you Jim, and I’m proud you left the same lasting impression on the soldiers you served with as the brothers you played rugby with. I’ll never forget you.”

The poster was “A Brother”. I didn’t ask which one.