The first time I went to the Glastonbury festival it healed me. Truly. It was 1994. Three weeks earlier I’d been attacked in the street of my university town, knocked to the pavement and kicked in the head several times. I woke up in hospital with bruises and concussion, then drifted through each day feeling sluggish and distant, like I was underwater. Still, I wasn’t going to miss my first Glastonbury. That would have been foolish.

I had managed to secure a last-minute ticket through a friend of a friend who played for the local rugby club in Glastonbury town. The club members volunteered as festival stewards and one of them was ill, so I took his identity and reported for work on the Friday, despite looking like a feeble excuse for a rugby player. After my first shift I was told to come back on Saturday night, but this was when the techno duo Orbital were playing. A dilemma.

This was the first year Glastonbury was televised and the last year that indie and dance music were confined to the second stage. It was also the only year the Pyramid stage burned down (before the site opened) and five people were shot (none fatally). I spent an unfeasibly magical day or so exploring the site and seeing bands with friends: the Beastie Boys, the Boo Radleys, Saint Etienne.

As Saturday evening came I gave my conundrum due consideration and went to see Orbital. The music played. My brain resurfaced. The world felt clear and bright and loud again. This embracing, forgiving place, surely, was the polar opposite of having your head kicked in. The next morning, the concussion was gone for good. I like to think that my fellow stewards and the innocent rugby player I was impersonating would agree that, on balance, it was the right thing to do. Neurologically speaking.

I don’t hold with talk of ley lines and sacred ground, but I do believe that Glastonbury is an endeavour that verges on the miraculous. It’s traditional to climb the hill to the Stone Circle at dawn and watch the entire site tremble in the morning mist, but it’s just as eye-opening to make the journey at dusk, when everyone is still awake and full of plans, and gaze down on a glittering, pulsing independent city of 200,000 souls.

In 1915 the American novelist and poet Hervey White staged his first festival at the Maverick arts colony just outside Woodstock, New York, and declared in the flyer: “There will be a village that will stand for but a day, which mad artists have hung with glorious banners and blazoned in the entrance through the woods.” Glastonbury takes this idea of a pop-up bohemian utopia to the limit: it stands for a week and has roughly the same population as Aberdeen, Geneva or Salt Lake City, with its own cinemas, pubs, restaurants, art exhibitions, streets, valleys, bridges and suburbs. Just consider how much thought, labour and dauntless optimism goes into creating a temporary community on that scale and making it run smoothly.

Certain media outlets would have you believe that Glastonbury is chiefly populated these days by posh girls in hotpants and Hunter wellies, but it contains multitudes: wide-eyed newbies and silver-haired veterans; early-risers and up-all-nighters; stag-weekend geezers and wispy flower-fairies; modern parents bearing babies in papooses and teenagers on drugs you’ve never heard of. It’s a dazzling sprawl of humanity united by the determination to have fun.

When I left the site in 1994 I didn’t imagine that I’d still be coming back 22 years later but I’ve only missed one festival since and it never feels like my last. In fact, last year’s – my 17th – was my favourite yet. I’ve spent many of the most joyful days of my life on this patch of Somerset. It’s where I become my very best self. There’s always a moment on Sunday when I’m so deeply attuned to the festival’s time-bending rhythms that it feels like this is my life now; that all I have to do is eat, drink, walk, talk and dance. Perhaps I have low horizons but I consider that a kind of bliss.

There are dozens more festivals in Britain each summer than there were in 1994, many of them fantastic, and yet Glastonbury’s special status has, if anything, grown. No doubt the sense of occasion has something to do with how hard it is to get a ticket – this year’s festival sold out in just 30 minutes – but even seasoned performers can seem overwhelmed by the experience. I’ve seen Leonard Cohen look on with stunned delight as tens of thousands of people sang Hallelujah at sunset; Damon Albarn sit down and weep at the end of Blur’s 2009 reunion show; Patti Smith exchange small talk with the Dalai Lama; Stevie Wonder sing Happy Birthday to Michael Eavis; Mark Ronson perform Uptown Funk with the aid of Mary J Blige, George Clinton and Grandmaster Flash. And that’s just on the two biggest stages.

Media coverage inevitably focuses on the headliners, giving the impression that people’s weekends hinge on whether or not they like Metallica or Kanye West. In reality, each Glastonbury-goer is the proverbial blind man attempting to describe an elephant by touching a single part of it. You can compare notes with friends on Sunday night and discover that you have had completely different but equally rich weekends. In 2004 a friend told me he wouldn’t be joining us for Paul McCartney on the Pyramid stage because Ceephax Acid Crew were playing in the Glade, and he enjoyed himself as much as we did. I’ve had as much fun in a tent listening to a DJ play two hours of Motown as I have watching the Rolling Stones or Underworld – maybe more.

Some people pride themselves on finishing the weekend without having seen a single band. To me that seems like attending the World BBQ Championship and sticking to the salad bar, but they seem happy. TV coverage gives the illusion of one coherent Glastonbury narrative, but really there are myriad Glastonburies. You get to choose your own adventure.

The festival has become a much bigger, slicker operation over the past 20 years. The toilets are nicer, the contingency plans for bad weather better, the food incalculably more inviting. The nightlife has been transformed. You used to have to rely, after midnight, on guerrilla sound systems or stalls with big PAs if you wanted to dance. Now there is an official rave village that throbs deep into the night. Unless you stay up long enough to meet the sun you will fall asleep to the sound of distant drums.

Some people complain that Glastonbury hasn’t been the same since it introduced a formidable new security fence to thwart gatecrashers, and partnered with big-beast promoters Mean Fiddler in 2002. It certainly used to have a wilder, more anarchic energy, with campfires studding the site like evidence of a rebel encampment. But it also had more crimes, fights and crowd problems. I remember being caught in a panicky crush on Webbs Ash bridge in 2000, the year an epidemic of fence-jumpers doubled the official capacity, and realising that the site could only handle so many people before something terrible happened. Faced with the risk of another Roskilde, where nine people died in a crush that year, and a local council ultimatum, the Eavises had no alternative.

The only thing I feel a little nostalgia for is the sensation of being merrily lost. Now that I need to review as many bands as possible, I have to timetable my weekend with a precision that makes air-traffic controllers look like an improv troupe. My 90s festivals were, inevitably, more chaotic. Because TV coverage was modest, you felt like you had to be there. Because mobile phones were an exotic luxury, you weren’t always sure where there was. If you camped with friends, you could at least bank on seeing them once a day. With anyone else your prospects of meeting up hinged on prearranged rendezvous (“Hot cider stall, 3pm”) which represented the triumph of hope over experience.

If you were new to the festival, then it felt like a labyrinth, especially after dark. On Saturday night in 1997 I set off to find Primal Scream in the dance tent. The first people I asked for directions said they had no idea where it was but were going to see Radiohead instead and would I like a beer? I only knew a handful of Radiohead songs but I took the path of least resistance and ended up seeing one of the festival’s all-time great performances by accident with two cheerful strangers.

Rumours abounded in the pre-3G days. During the 1990s, reports of Cliff Richard’s death were a mischievous annual ritual. (Why Cliff? I never knew.) In 2003 someone confidently informed me that Saddam Hussein had been captured, six months before he actually was. Even in the smartphone era, misinformation about the festival itself thrives. In 2013 the grapevine buzzed with reports of a secret afterhours Daft Punk set in one of the outer fields. I patiently explained to more than one person that a duo who had just released the most painstakingly crafted and presented album in recent memory, and hadn’t played live since 2007, were about as likely to pop up unannounced as, well, Saddam Hussein, but they didn’t want to know. At Glastonbury, people like to believe in impossible things.

I realise Glastonbury is not for everybody. At the very least you have to feel a certain affection for crowds. You need to accept that occasionally people will crash into you, prattle their way loudly through your favourite band, make drug-spangled conversation while their eyeballs attempt to flee their heads or, as happened on one occasion, drunkenly spin around while urinating on anyone within range, like some foul lawn-sprinkler.

If you can’t manage a little rough-and-tumble you will have a thin time of it. One year I was at the Pyramid stage with a comically tense American who hadn’t yet acclimatised to the festival’s freewheeling etiquette. When a drunk man blundered into him with an amiable “Sorry mate”, the unquiet American turned on him like Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy: “Hey buddy! What the fuck are you doing?” I hope he came back one year and relaxed enough to drunkenly stumble into someone himself. Glastonbury is no place for “Hey buddy!”

You also need to be stoical in the face of bad weather. In 1997 I remember watching the Chemical Brothers with my wellies stuck so fast in the mud that I could only dance from the knees up. The following year it rained so hard that sheltering under a tree actually made things worse because the sodden branches decanted water on to your head. But at least I wasn’t in the dance tent when the operator of a sewage truck pressed the wrong button and, instead of extracting excess mud from the tent, pumped a torrent of human waste into it.

In 2005 when a freak overnight downpour connected with dry ground, I saw a river spring up to the side of the Pyramid stage and dozens of tents slide sadly down a waterlogged hill. In 2007 my wife and I spent three days watching bands through a forest of umbrellas, then needed a pick-up truck to extract our car from the sucking ooze of what was once a car park. That wasn’t a vintage year if I’m being totally honest.

When it’s too hot, on the other hand, you wake up sweltering at dawn and fall asleep, gently roasting, in the middle of the afternoon. Sometimes the weather is just drab and noncommittal. The first time I tried to watch dawn from the Stone Circle, clouds erased the sun and the only thing I can remember seeing, when I turned my head at the wrong time, was a naked man’s shivering balls.

The upside of Glastonbury’s climatic challenges is that they weed out the time-wasters. If you can’t stomach camping, mud or (still) the occasional toilet that resembles a scene from Se7en, then don’t come. It’s always sunny at Coachella… and look at the glib dilettantes you get there. You have to work a bit harder at Glastonbury, and the extra effort has a bonding effect. Yes, it’s startlingly expensive compared to its Aquarian origins in 1970 – and you don’t even get free milk – but have you seen the price of arena gigs lately? Even if you only see a few bands a day you’re in the black.

Countless performances are burned into my brain. Al Green singing Let’s Stay Together on Glastonbury’s first sunny Sunday afternoon in four years. The nascent Killers filling the John Peel tent to overflowing. Coldplay and Basement Jaxx both covering Can’t Get You Out of My Head after a seriously ill Kylie pulled out. Beyoncé singing At Last in tribute to Obama and the civil rights movement. 2 Many DJs unexpectedly playing Supergrass’s Britpop knees-up Alright beneath the Arcadia field’s colossal, fire-breathing robotic spider. The crowd sustaining the final lines of Karma Police over and over as Radiohead left the stage.

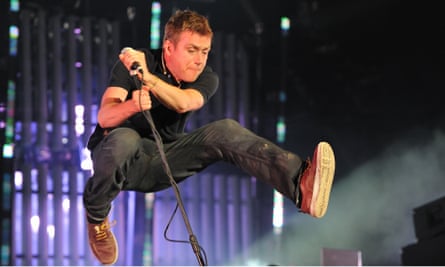

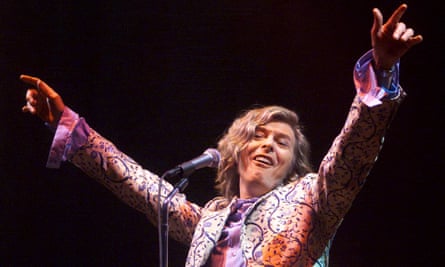

And more. Bowie’s spectacular, career-reviving return to Glastonbury after 29 years. Jay Z silencing his critics with a barbed version of Wonderwall. Elbow vaulting into the premier league. The Prodigy in their lunatic pomp. The Pet Shop Boys’ giddy greatest hits set. Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ shamanic Stagger Lee. Mary J Blige’s storm-lashed No More Drama. Neil Young’s monstrous Down By the River. Hot Chip’s ecstatic cover of Dancing in the Dark. Goldfrapp’s crotch-mounted synthesizer. Janelle Monáe’s hotstepping funk revue. Brian Wilson’s sunshine symphonies. The Stooges’s swampy stage invasion. Portishead’s anti-Trident protest. U2’s space-station video link. The Flaming Lips’s furry freaks. Lana Del Rey’s Novocaine insouciance. Father John Misty’s black comedy. Dolly Parton’s showbiz masterclass. James Brown’s cape routine. Björk’s lasers.

For all that, some of my favourite memories of Glastonbury aren’t the performers but the more eccentric punters. Like the Bowie fan who took a lusty snort of amyl nitrate before every song and got so excited during Starman that he took two, turned pale and tumbled through the crowd with a strangled cry of “Staaarrmaaaaan!”. The man who cycled around the site in an Elvis mask, towing a boom box that played a constant loop of Free Nelson Mandela. (At this point Nelson Mandela had been free for some time.) The Clash-oblivious teenager who confidently told his friend that the Strummerville area was thus named because “There was this guy called Joey Strummerville who loved building fires and then he died.” The poor soul who brought along a full-size green door in expectation of Shakin’ Stevens’s appearance and bore it aloft throughout a set that signally failed to include the song Green Door.

Then there are the doughty flag-wavers who give the Pyramid field the aspect of a ragtag medieval army. The flamboyantly heterodox dancers who turn the late-night fields into a panoramic celebration of club culture through the years. The mud-bathing Morlocks. The artists, the activists and the hippies. (Who knew there were still so many hippies? Where do they hide the rest of the year?) I am never more tolerant, more empathetic, more in love with the human project than I am at Glastonbury. Basically, as long as you’re not urinating on me, follow your arrow.

Since we’ve had children, people keep asking us if we’re planning to take them to Glastonbury one day. The short answer is: “Jesus Christ, no.” The longer answer is that it would narrow our options somewhat. The nobler answer – also true – is that I’d rather our daughters discovered it for themselves when they’re old enough. I’m sure lifelong Glastonbury-goers like Lily Allen would disagree, but it seems like it would be more fun to plunge in at the deep end as an autonomous teenager than to warm up by tagging around with your parents for a few years.

I suppose I like the idea of them experiencing such a vast, multifarious, potentially life-changing phenomenon as free agents, able to do whatever brilliant, ridiculous, possibly unwise things they choose. If we’ve bowed out by then, I look forward to seeing them walk through the door on Monday, tired, grimy and elated. If we’re still going, I look forward to bumping into one of them somewhere in the infinite variety, exchanging a quick hello and watching her wander off into a Glastonbury of her own invention.

Or maybe I’ll be a wistful old bore banging on about that time Orbital cured my concussion. The options are endless.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion